2 years ago

Wednesday, December 28, 2016

Wednesday, December 21, 2016

Winter Solstice: A New Cycle Begins

The

wonderful aspect of anything cyclic is that at the end, we always return to the

starting point. For Earth’s solar year, many consider that starting point to be

Sun’s nadir in the Northern Hemisphere, the paradoxical darkest night that is

also the symbolic birthday of the Sun.

For

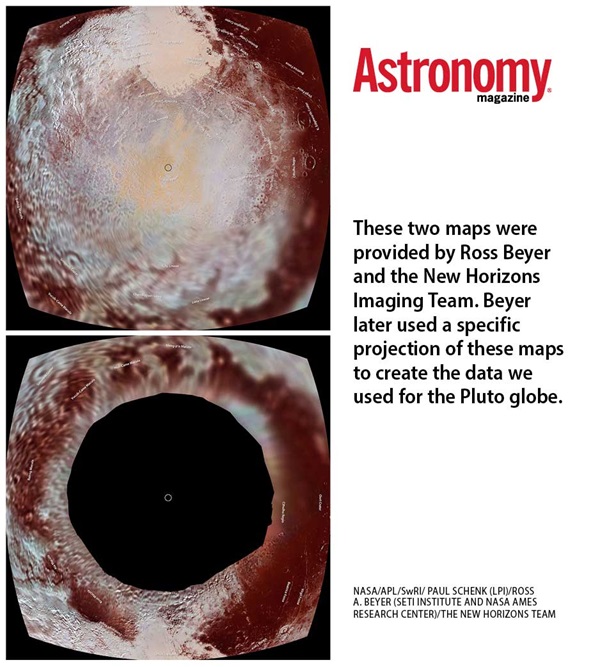

space and astronomy, it has been a tremendous year. New Horizons finished

sending back all data taken during the Pluto flyby, and the studying of that

data has only just begun. Pluto appears to be one of the solar system’s many

water worlds—planets and spherical moons with subsurface liquid oceans that

could potentially harbor life.

The

abundance of these water worlds in our solar system has been an ongoing theme

of discovery this year.

We’ve

learned about Ceres, Enceladus, Europa, Titan, and Mars; we’ve discovered a

planet orbiting Proxima Centauri, one of three stars that comprise the nearest

star system to our own, and we’ve continued to find more strange and unusual

exoplanets in places many thought they could not exist.

But

in the broader world, it has been a difficult year. Much attention has been

given to those things that divide us even as our own planet has passed

dangerous climate thresholds that should be uniting us in an effort to preserve

its habitability for humanity and for its many other species.

Winter

Solstice is a time for transcending divisions, a time that naturally brings us

together because we all experience the cold and dark. It reminds us that our

lives and our fates are intertwined with that of our home planet, that whatever

we do to the Earth, we do to ourselves.

And

just as we all experience the cold and the dark, we all long for the warmth and

the light. For thousands of years, this has been considered a time of miracles

because collectively, we experience the greatest miracle of all, the renewal of

our source of life—the Sun—from its weakest point.

Just

as the Moon appears to grow from nothing to crescent to half to gibbous to full,

then wane back through those phases to the point of disappearance, so the Sun

appears to go through a cycle of waxing to its prime, then waning back to near

disappearance. In that moment of transition from dark to new, a new cycle,

whether month (lunar) or year (solar) begins.

Many

astronauts who have had the good fortune to observe the Earth from space emphasize

the powerful, profound experience that is. Out there, no national or ethnic

boundaries are visible, just one beautiful blue, fragile marble floating in the

darkness.

Until

most of us get the chance to venture to space, the closest we can come to this

experience are beautiful pictures and videos and experiences like the seasonal

markers to bring us together, to remind us that we are all one planet.

Here

is hoping that this new year that starts as the Sun begins waxing again is one

in which we genuinely experience, appreciate, and value that awareness.

Happy

Solstice!

Tuesday, December 6, 2016

Thursday, December 1, 2016

Friday, November 4, 2016

Wednesday, October 26, 2016

DPS/EPSC update on New Horizons at the Pluto system and beyond

DPS/EPSC update on New Horizons at the Pluto system and beyond: Last week's Division for Planetary Sciences/European Planetary Science Congress meeting was chock-full of science from New Horizons at Pluto.

Thursday, October 20, 2016

Wednesday, October 12, 2016

Alan Stern and the New Horizons Team Receive Cosmos Award

Alan Stern: Alan Stern and the New Horizons mission team are the newest recipients of The Planetary Society's Cosmos Award for Outstanding Public Presentation of Science.

Tuesday, September 27, 2016

Monday, September 19, 2016

Wednesday, August 24, 2016

Pluto: Ten Years Since the IAU's Epic Fail

After

the 1920s debate over whether the universe is composed of one galaxy—the Milky

Way—or of many galaxies was resolved with definitive evidence for the latter

position, the controversy was resolved.

Our

universe contains billions of galaxies, including structures once referred to

as “spiral nebulae” erroneously thought to be located within the Milky Way.

After

observations conducted during the May 1919 total solar eclipse confirmed

Einstein’s theory of general relativity, showing the position of stars near the

Sun slightly shifted from their actual locations, general relativity was

accepted worldwide as being true—and as the reason for the strange precession

of the planet Mercury’s perihelion (point closest to the Sun).

But

ten years after the controversial and highly problematic planet definition

adopted by four percent of the IAU, most of whom were not planetary scientists

but other types of astronomers—that definition remains as contested as it was

on day one.

Rather

than bringing a resolution to the debate, as did the evidence in the two

previous examples, the IAU vote heightened that debate and resolved nothing.

It

actually did harm to science by confusing the public into thinking science is

done by voting and by imposing a definition that contradicts everything people

see when observing close-up photos of Pluto.

Back

in 2006, no such close-ups of Pluto existed. However, the IAU knew fully well

that the New Horizons probe, launched seven months before that year’s General

Assembly, was on its way to Pluto and would provide a wealth of images and data

in July 2015.

They

also knew that the Dawn mission was scheduled for a launch the following year,

and it would visit Ceres and Vesta, two objects that orbit between Mars and

Jupiter, both of whose statuses as asteroids were questionable.

The scientifically

correct action would have been to wait until the data from these missions came

in before trying to classify objects no one ever viewed as more than tiny dots.

Unfortunately,

several astronomers, motivated by their own personal agendas, did not want to

wait for the results. Leading that group was the late Dr. Brian Marsden, who

had expressed his desire to see Pluto demoted from planethood to discoverer

Clyde Tombaugh back in 1980.

When

a team of three astronomers discovered a planet beyond Pluto initially thought

to be bigger than Pluto, now known as Eris, some of these astronomers jumped at

the opportunity to use the discovery as a means of imposing their agenda.

They

claimed that if the new object is larger than Pluto and yet is not a planet,

then Pluto could not be a planet either.

In

2010, when Eris occulted a star, a different group of astronomers led by Dr.

Bruno Sicardy determined it is marginally smaller than Pluto though 27 percent

more massive.

Even

if Eris were larger than Pluto, why would its discovery prompt any sense of necessity

to come up with a specific definition of planet? So what if our solar system

has 10 planets or 11, or 50? Most people actually find it exciting to learn

that the solar system has many more planets than anyone ever thought.

What

should have happened is that Eris should simply have been added as yet another

solar system planet.

But

in addition to personal agendas, some astronomers came up with the ridiculous

idea that our solar system cannot have “too many planets” because kids won’t be

able to memorize all their names.

That

argument is no more rational than stating we have to limit the number of stars

and galaxies to something countable, or that we have to limit Jupiter’s moons

to four because no one can memorize the names of 67.

Memorization

is not critical to learning. Once upon a time, little was known about the

planets other than their names, their order from the Sun, and estimates of

their sizes. At that point, there wasn’t

much else to teach about them.

Today,

things couldn’t be more different. With the dawn of the space age, we have

robotically visited every single one of the nine classical planets as well as

Ceres and Vesta. We know the complex processes many of them and many of their

moons undergo, their compositions, and their surface features.

Instead

of asking children—and adults—to memorize a list of names, we can teach them

the characteristics of the different subclasses of planets such as

terrestrials, gas giants, ice giants, dwarf planets, proto-planets, super

Earths, hot Jupiters, hot Neptunes, etc.

The

latter three are not present in our solar system but do exist in other star

systems.

Ten

years ago, in essence, the IAU concocted a reason to issue a decree that was

never needed. Its members then set out to craft a definition that achieved the

results they desired, namely excluding Pluto.

And

they established a definition with a requirement that set Pluto’s status in

stone. No matter what would be discovered by New Horizons, Pluto could never

again be a planet because its intrinsic characteristics meant nothing. The only

thing that counted was whether it cleared its orbit.

Orbit

clearing may be useful in terms of understanding the effects celestial objects

have on other objects, but making it a requirement for planet status makes

absolutely no sense.

The

further an object orbits from its parent star, the larger an orbit it has to

clear. That makes the definition inherently biased against planets in distant

orbits from their stars.

Furthermore,

it perpetuates an erroneous conception of objects like Pluto and Ceres, leading

people to think these worlds are surrounded by numerous objects in their orbits

in an asteroid field similar to the one through which Luke Skywalker piloted

the Millennium Falcon in Star Wars.

Yet

nothing could be further from the truth. Both the asteroid and Kuiper belts are

huge, with vast distances between objects residing in them. This is why New

Horizons did not have to use one of its contingent trajectories to fly through

the Pluto system. Those trajectories were based on a need to avoid debris that

might be floating around near Pluto.

But

there was no such debris, which New Horizons scientists attribute to Pluto’s

large moon and binary companion Charon having swept it all from the system.

If

KBOs were really so close to one another in a crowded belt, why could only the

Hubble Space Telescope find a few close enough KBOs in New Horizons’ path for a

visit after Pluto? From the way people talk about the Kuiper Belt, one would have

thought there were numerous small objects nearby.

Haumea,

Makemake, Eris, and other, more recently discovered dwarf planets are not in

Pluto’s orbit unless one counts the entire Kuiper Belt as part of Pluto’s orbit—a

proposition that makes no sense, as the belt is huge, and the majority of it is

located well beyond Pluto.

Yet,

because of the IAU definition, many people are under the misconception that

many objects larger than Pluto have been discovered in the Kuiper Belt and that

the entire region is a zone crowded with ice balls and rocks.

While

there could be planets larger than Pluto out there, so far none has been

discovered.

Astronomer

Mike Brown, who co-discovered Eris, earlier this year publicly hypothesized the

existence of a large planet far beyond Pluto, which, to add insult to injury,

he deliberately referred to as “Planet Nine,” clearly for no other reason than

to snub those who still consider Pluto a planet.

Now,

when we have a wealth of data and images about Pluto, certainly sufficient new

information to re-open the planet debate yet again, the IAU has no interest in

doing so. Why does some new data in 2006 justify IAU action yet a huge

inundation of new information in 2016 not inspire similar action?

It

is not just the IAU that is at fault here. The media has been misrepresenting

this issue for a decade now. From day one, they should have questioned the IAU

definition and consulted the many planetary scientists who signed a petition

disagreeing with it. Instead, they reported the decision as fact, calling Pluto

an “ex-planet,” and stating that textbooks and teachers now have to change

their teaching of the solar system to one of eight planets.

The

media also unprofessionally blindly accepted Brown’s use of the term “Planet

Nine” for the hypothesized large planet yet to be discovered when what they

should have done is referred to it by the standard appellation for undiscovered

worlds, which is “Planet X.”

Where

the media failed big time is in accepting the IAU decree at face value instead

of critically pointing out that science is not determined by “authority” but by

a preponderance of evidence for a theory or position.

They

also failed to inform the public that most of the 424 IAU members who voted in

2006 were specialists not in planetary science but in completely different

fields of astronomy. Why would a person who studies black holes be considered

an expert on planetary science? Would the media accept a decree by planetary

scientists about the nature of black holes?

The

fact that the IAU definition is still so contentious a decade after its

adoption is itself evidence that it was and is an epic fail.

Interestingly,

even children born after the vote still consider Pluto a planet. When I worked

as a performer in the New Jersey Renaissance Faire playing a court

astronomer/astrologer, I asked children what their favorite planet was, and

Pluto was the number one answer, followed by Earth.

That

is usually when I shared that in the 1560s, calling Earth a planet was

considered controversial, as it amounted to an affirmation of Copernicanism,

which stated the Sun is the center of the solar system and the Earth simply a

planet orbiting the Sun.

New

Horizons Principal Investigator Alan Stern reports that the status issue is

raised at every single talk he gives about New Horizons and Pluto, even if he

does not mention the controversy in his presentation.

Because

planetary scientists do not have a formal organization like the IAU, they do

not have a means to organize and promote an alternative point of view. That,

however, does not mean that that alternative view does not exist.

As

for the claim that Pluto cannot be considered a “major planet” due to its small

size, the real problem is the false dichotomy inherent in using the terms “major”

and “minor” planet. As David Weintraub notes in his book Is Pluto A Planet, the term “minor planet” has been used for more

than a century to refer to asteroids and comets, objects too small to be

rounded by their own gravity. These are the objects the IAU accurately refers

to as “Small Solar System Bodies.”

But

Pluto and Ceres—and all dwarf planets—are not asteroids, so the term “minor

planet” is not appropriate for them. A better schematic is to do away with the

terms “major” and “minor” planet altogether and replace them with terrestrials,

jovians, and dwarf planets, all of which fall under the umbrella of planets.

Objects like Vesta and Pallas, which are larger and more complex than

asteroids, could comprise yet another planetary subcategory, “proto-planets.”

A

decade after a controversial vote allegedly changed everything about the way we

understand our solar system but really changed nothing, planetary scientists, professional

and amateur astronomers, and members of the public overwhelmingly continue to

view Pluto as a planet, especially in light of the geologically complex world

New Horizons found.

Public

usage, not a decree from an isolated, self-appointed group of “experts,” will

determine which view enters into posterity. From the last ten years, it is

clear that when it comes to Pluto, that view will not be the one advocated by

four percent of the IAU.

Adored

worldwide, the little planet that would not die is so very special that it will

be there for eternity.

Saturday, August 13, 2016

Monday, July 18, 2016

Friday, July 15, 2016

Pluto Flyby, One Year Later

Can

it really be a year since that fateful, long-anticipated, wondrous day, July

14, 2015, when New Horizons flew by Pluto, giving humanity its first detailed

glimpse of that mysterious world? One commenter on Facebook said it seems like

just a few months, a sentiment that I share.

One

year ago, after a journey of nine-and-a-half years and three billion miles, the

world witnessed the culmination of a dream that began 25 years earlier and of

two-and-a-half decades of persistence by Pluto scientists to make that dream a

reality.

One year

ago, on one of the most exciting days of my life, I joined thousands of

cheering supporters in a New Year’s Eve-style countdown beginning with “9”

instead of “10,” to 7:49 AM, the moment of the spacecraft’s closest approach.

About 13 hours later, I celebrated with a tired but exuberant crowd at mission

headquarters in Laurel, Maryland, as the spacecraft’s signal that it had

successfully traversed the Pluto system arrived.

I

was blessed to have the opportunity to cover the mission for the website “Spaceflight

Insider,” which allowed me to attend as media and spend the interim hours in

the media area, both writing and talking with scientists and journalists from

around the country and the world.

After

the moment of closest approach had passed, the New Horizons team shared a

fascinating finding with us. It was official: Pluto is bigger than previously

thought, marginally bigger than Eris. In the long run, that might seem trivial,

but it put a definitive end to the claim that Eris is bigger, and if it cannot

be classed as a planet, neither can Pluto. The 2006 estimates of Eris’s size

were wrong; Bruno Sicardy’s 2010 measurements were correct.

We

also were shown the last photo of Pluto sent back before the encounter, so in

case the worst happened, and the spacecraft was destroyed by impact with

debris, at least the mission had some images successfully returned.

It

was a beautiful image, with the heart feature, Tombaugh Regio, front and

center.

Since

then, Pluto has continually surprised everyone, both scientists and lay people.

Numerous predictions were proven wrong. Pluto is not a highly cratered, dead

world but a geologically active one. Its atmosphere is not escaping as it

recedes from the Sun. It has floating mountains and glaciers, ice volcanoes,

and very likely a subsurface ocean.

Pluto’s

interaction with the solar wind is far more like that of the larger planets

than like that of a comet.

Ironically,

every discovery has seemed skewed toward the characteristics of planet, almost

as if Pluto itself were having the last laugh in response to a small number of

astronomers who attempted to classify it without even seeing it.

And

the world became enchanted with Pluto, which made the covers of numerous

newspapers and magazines. Even Google did a special doodle for the flyby.

The

only ones who didn’t seem impressed were those who attended the IAU General

Assembly one month after the flyby. Their biggest concern was that the New

Horizons team was using names for sites on Pluto and its moons without “official”

IAU approval.

Those

wedded to the notion that a planet must “clear the neighborhood of its orbit”

wrote numerous articles stating that the flyby showed an object does not have

to be a planet to be interesting. And therein, they missed the point. All the

features and processes revealed by New Horizons are those of planets. Yet

somehow, none of these intrinsic factors matter to those whose minds are made

up.

By

making “clearing its orbit” a requirement for planethood, four percent of the

IAU essentially assured that no matter what is happening on Pluto’s surface and

atmosphere, no matter what the New Horizons mission found, Pluto would forever

be precluded from being classed as a planet and their position would always “win.”

That

might be a clever political move, but it certainly is not a smart scientific

one, especially since it amounts to reaching a conclusion first and only

afterwards making sure the evidence fits that desired conclusion.

The

fact that New Horizons flew by the Pluto system without encountering any debris

actually calls the claim that it doesn’t clear its orbit into question. Pluto’s

immediate vicinity was likely cleared of debris by its large moon and binary

companion, Charon.

An “un-cleared”

orbit calls to mind the asteroid field navigated by Luke Skywalker in The Empire Strikes Back, where the Millennium Falcon has to weave and dodge

to avoid hitting the many asteroids clustered together. This was hardly the

case for New Horizons as it flew through the Pluto system.

One

has to ask, do those who require “orbit clearing” see the entire Kuiper Belt as

Pluto’s “neighborhood?” The Kuiper Belt is huge, most of it stretching far

beyond Pluto. The New Horizons team needed to use the Hubble Space Telescope

just to find an object on the spacecraft’s trajectory to visit after Pluto, and

that object is a billion miles beyond the planet!

Eighty

percent of the data from last year’s flyby is now back, and the remaining 20

percent is expected to be returned sometime this fall.

Pluto

so thrilled and excited the world that there already has been talk of

returning, this time with an orbiter. Principal investigator Alan Stern told

the audience at this spring’s Northeast Astronomy Forum (NEAF) that the

technology for an orbiter already exists.

To

get the ball rolling on a potential orbiter, advocates need to make it a

priority in the next Decadal Survey, a list of goals prepared under the

guidance of the National Research Council once every ten years.

NASA

will start outreach to the council in 2018 or 2019 to begin this process, with

the next Decadal Survey expected to be released in 2022. This means it is not

too early to start seriously advocating a return to the Pluto system.

“I

think Pluto is indeed an object we’re going to need to know more about,” NASA

Director of Planetary Science Jim Green said last year.

“I

think the excitement is there, the details, in terms of the science, will come

out…and they’re going to be pushing for what might be the next steps, you bet.”

For

now, to celebrate this momentous anniversary, the New Horizons mission has

published a list of its top 10 Pluto pictures, a survey of its top ten

discoveries from the flyby, and a stunning video compiled from more than 100

images taken during approach simulating what one would see upon arriving at the

planet.

“Just

over a year ago, Pluto was a dot in the distance. This video shows what it

would be like to ride aboard an approaching spacecraft and see Pluto grow to

become a world, and then swoop down over its particular terrains as if we were

approaching some future landing on them,” Stern said.

Enjoy!

Friday, July 1, 2016

New Horizons Receives Mission Extension to Kuiper Belt, Dawn to Remain at Ceres

New Horizons Receives Mission Extension to Kuiper Belt, Dawn to Remain at Ceres: Following its historic first-ever flyby of Pluto, NASA’s New Horizons mission has received the green light to fly onward to an object deeper in the Kuiper Belt, known as 2014 MU69.

Thursday, June 23, 2016

Thursday, June 2, 2016

What's Over the Horizon? - Fall/Winter 2015

What's Over the Horizon? - Fall/Winter 2015: AS HARVEY MUDD STUDENTS SETTLED INTO THEIR dorms to start the 2009–2010 academic year—some a tad homesick no doubt—Pluto-bound spacecraft …

Tuesday, May 31, 2016

Wednesday, May 25, 2016

Tuesday, May 3, 2016

Good Article on the State of the Pluto Planet Debate

This is a good article that presents both sides of the planet debate with up to date information, including quotes from Alan Stern. Check out the comments too!

https://www.theguardian.com/science/2016/m

Friday, April 22, 2016

Monday, March 21, 2016

Thursday, February 18, 2016

86 Years After Discovery, Data Shows Pluto is a Planet

Today

marks the 86th anniversary of the discovery of planet Pluto in 1930

by 24-year-old Clyde Tombaugh at the Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona.

Sometime

around 4 PM on that day, while using a blink comparator to move between two photographic

plates depicting the same part of the sky taken several days apart a month

earlier, Tombaugh detected a tiny dot that moved against the background stars.

That

dot was Pluto. The fascinating story of its discovery is described here: http://pluto.jhuapl.edu/Participate/learn/What-We-Know.php?link=Discovery-of-Pluto

.

“I

have found your Planet X,” the young astronomer told Lowell Observatory director

Vesto Slipher, ending the decades-long search for a trans-Neptunian planet

initiated by observatory founder Percival Lowell.

Over

the past year, we have had the opportunity to do what Clyde Tombaugh could only

dream of—transform that tiny dot he found, not even large enough to be resolved

into a disk with the most powerful telescopes of the day—into a living, breathing

planet.

We

are now into the “Year of Pluto 2,” and the amazing images and information keep

coming and will continue to do so through most of this year.

This

anniversary is an appropriate occasion to re-examine, in light of all these new

findings, the claim that Pluto is somehow “different” from the solar system’s

eight larger planets.

Let’s

start with the often repeated, “Pluto is very different from the ‘big eight.’”

First,

there are no “big eight,” unless one lumps together two very different types of

worlds—the rocky, terrestrial planets on one hand, and the gas giants and ice

giants on the other.

Any

classification system that puts Earth and Jupiter in the same category but

excludes Pluto overlooks an important fact, specifically, that Earth has far

more in common with Pluto than it does with Jupiter.

Gas

giants Jupiter and Saturn and ice giants Uranus and Neptune have no known solid

surfaces. Both have extensive systems of rings and moons that are almost their

own “mini-solar systems.” Jupiter and Saturn are composed primarily of hydrogen

and helium, much like the Sun.

Like

Earth, Pluto is rocky and geologically differentiated into core, mantle, and

crust. Like Earth, it is geologically active. It has far more water ice than

previously thought, and its geological processes suggest an internal heat source

that could possibly support a subsurface ocean.

Some

scientists see evidence for such an ocean in the faults and fissures on Pluto’s

surface and in the planet’s lack of an equatorial bulge.

Equatorial

bulges are created by the spin of rotating spherical objects. Because water

moves more easily than ice, an underground ocean would reduce any bulge by acting

against rotational forces.

Both

Earth and Pluto have nitrogen in their atmospheres. The only other solar system

world with a nitrogen atmosphere is Saturn’s moon Titan.

Both

Earth and Pluto have large moons formed via a giant impact very early in the

solar system’s history.

Pluto

was initially thought to be larger than it is because until 1978, scientists

did not realize they were looking at two objects rather than one when they

observed Pluto through a telescope. The planet and its largest moon Charon,

which is half its size, are separated by just 12,196 miles (19,640 km), the

smallest separation between any planet and moon in the solar system.

And

because Pluto and Charon orbit a center of gravity, known as a barycenter,

outside of Pluto, between the two objects, they can genuinely be considered a

double or binary planet system.

New

Horizons’ findings indicate Pluto actually has more in common with Earth than

anyone imagined.

Instead

of the dead world many expected, Pluto has revealed itself to be “a world of

unexpected complexity and riches,” mission principal investigator Alan Stern

commented.

Among

the small planet’s stunning array of terrains are wind-blown dunes similar to

those on Earth and on Jupiter’s moon Europa. Worlds with atmospheres as thin as

Pluto’s do not usually have dunes, suggesting Pluto’s atmosphere may once have

been a lot thicker.

Pluto’s

famous “heart,” named Tombaugh Regio for discoverer Tombaugh, has a young

surface with no craters.

Ice

floating on the left side of side of Tombaugh Regio, known as Sputnik Planum,

flows in a manner similar to the movement of glaciers on Earth. Only two other

worlds in the solar system, Earth and Mars, experience this type of activity.

The

fact that Sputnik Planum’s terrain is constantly being reshaped suggests

tectonic forces (geological forces that cause movements of a planet’s crust)

are at work, possibly caused by internal heating produced through radioactive

decay of rocky material in Pluto’s core.

“The

Pluto system surprised us in many ways, most notably teaching us that small

planets can remain active billions of years after their formation,” Stern said.

Pluto’s

layered, atmospheric haze is similar to that seen on Titan. It is also far more

complex than scientists anticipated. Pluto’s sky appears blue at sunrise and sunset

because its haze particles scatter blue light. Which other planet has a blue sky?

Two

mountains on the Pluto’s encounter side (that observed in most detail by New

Horizons), Wright Mons and Picard Mons, appear to be ice volcanoes, also known

as cryovolcanoes. These mountains have broad, gentle slopes, characteristic of

what are known as shield volcanoes.

The

only other shield volcanoes in the solar system are on Earth and Mars.

Pluto’s

active geology and possibly cryovolcanism could be driven by a mix of ammonia

and water ice in its mantle.

Located

between the inner crust and outer core, that mantle may be experiencing

convection, a process through which hot material rises up while cooler material

sinks down.

On

Earth, convection drives the movement of tectonic plates.

Networks

of eroded valleys on Pluto’s surface, described by some scientists as “hanging

valleys,” resemble similar features seen on Earth in Yellowstone National Park.

The

point in emphasizing these detailed features is that Pluto may have more in

common with Earth than with any other solar system planet.

The

abundance of water ice on its surface and the possibility of a subsurface ocean

add Pluto to the solar system’s leading contenders for microbial life, a list

that includes Europa and Saturn’s moon Enceladus, both of which are believed to

have subsurface oceans.

Data

sent back by New Horizons just this week indicates Charon, which is also

geologically active, once had a subsurface ocean too.

Nine

and a half years ago, four percent of the IAU decided they knew how to best

classify Pluto in spite of the fact that they had never seen it up close and

knew nothing of its features. Even today, apologists for the IAU claim that

their decision stands, that Pluto is not a planet because astronomy’s “ruling

authority” said so.

Yet

Pluto’s surface and atmosphere tell a very different story.

"I

naturally refer to Pluto as a planet because that seems like the right moniker,”

New Horizons project scientist Cathy Olkin states. “It has an atmosphere; it

has interesting geology; it orbits the sun; it has moons. ‘Planet’ just seems

right to me."

Friday, January 29, 2016

Thursday, January 21, 2016

Super Earth May Exist, but It's NOT "Planet Nine"

The

potential discovery of a Super Earth in the outer solar system made huge

headlines today. Inferred from the eccentric orbits of several tiny objects in

the Kuiper Belt, this planet is estimated to orbit 19 billion miles or 200

astronomical units (AU) from the Sun, with one AU equal to the Earth-Sun

distance of approximately 93 million miles.

This distant world, which would take between 10,000 and 20,000 years to orbit the Sun, is estimated to have a mass ten times that of the Earth.

Significantly,

this planet has not been observed or actually detected. Its existence is

inferred solely through computer simulations.

Unfortunately,

one of the two scientists conducting the study, Mike Brown, who has spent a

decade obsessed with the very unprofessional claim that he “killed” planet

Pluto, decided to take a page from the presidential candidates and use this

possible discovery to promote his own personal agenda.

He

did this by naming the potential object “Planet Nine,” a deliberate affront to

those who reject the IAU planet definition just one day after the tenth

anniversary of New Horizons’ launch.

By

using this name on a press release distributed to countless media outlets,

Brown assured that his version of the solar system would be repeated again and

again in article headlines as the only view of the solar system.

It is a view based on the highly emotional, unscientific premise that our solar system cannot have “too many planets,” so artificial lines have to be drawn to keep the number of planets small.

By referring

to any new planet discovered as “Planet Nine,” he is inherently denying the

existence of the ongoing debate over planet definition and over the number of

planets our solar system has.

According

to the geophysical planet definition, held by many planetary scientists, a

planet is any non-self-luminous celestial spheroidal body orbiting a star, free

floating in space, or even orbiting another planet. If an object is not a star

itself and is large enough and massive enough to be rounded by its own gravity,

it is a planet.

That

means, as I have often stated before, that dwarf planets are planets too. Alan

Stern, the person who coined the term “dwarf planet” intended it to refer to a

third class of planets in addition to terrestrials and jovians.

According

to this definition, there is no requirement that an object “clear its orbit” to

be considered a planet.

So

for the many scientists and members of the public who adhere to the geophysical

planet definition, our solar system has a minimum of 13 planets, 14 if we count

Charon as part of a binary system with Pluto. In order from the Sun, these are

Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Ceres, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, Pluto,

Charon, Haumea, Makemake, and Eris.

Inner

Oort Cloud Object Sedna and the recent, distant discovery known as 2012 VP113

and nicknamed “Biden,” are likely spherical as well, raising that count to 16. As

Alan Stern noted, “If they do find it

(this proposed object), it’ll be more like Number 19, not Number 9.”

Unfortunately,

very few media outlets chose to seek the geophysical point of view. Instead,

most simply more repeated the nonsense that Brown is “the Pluto Killer” and

quoted only him and his research partner, Konstantin Batygin.

And

Brown made sure to get in as many digs at Pluto and at denying the existence of

the ongoing planet debate as possible, making statements such as, “There have

only been two true planets discovered since ancient times, and this would be

the third.”

Over

and over, he presented his opinion as fact, and few journalists even thought to

question it. From the geophysical view, more than two planets have been

discovered since ancient times because Ceres, Pluto, Haumea, Makemake, and Eris

are true planets too.

Brown

and Batygin supposedly considered other names for this possible new object,

including George, Planet of the Apes, Jehoshaphat and Phattie. Any one of these

would have been better than “Planet Nine,” which is not really a name but a

statement saying his view of the solar system is the only view.

Most

following the New Horizons mission now know just how much of a planet Pluto is.

It is more geologically active than Mars and has features such as flowing ice

and likely cryovolcanoes, which strongly suggest an internal heat source no one

anticipated.

There

is complex interaction between its atmosphere and surface, and there may even

be an underground ocean that could harbor microbial life. A good number of New

Horizons scientists have commented that given these features, there isn’t

anything else they can call this world other than a planet.

None

of this apparently makes any difference to Brown, but then again, he doesn’t

study Pluto. So insistent is he on the controversial “requirement” of orbit

clearing that he states of the potential discovery, “The fact that it could

affect the orbits of other objects over such a wide area would make it “the

most planet-y of the planets in the whole solar system.”

Why

should an object’s effect on other objects make it more “planet-y” than its

intrinsic properties?

Theories

positing the existence of a large planet far beyond Pluto have been around for

a long time. Announcing that a computer simulation points to this possibility is

an ideal opportunity to excite the public about space exploration and what

might be out there.

Instead,

Brown effectively hijacked this story to promote himself, his imagined

accomplishment of having “killed” Pluto, and his subjective view of our solar

system, conveniently ignoring that his view is just one in an ongoing debate.

The

first principle of propaganda is, “A lie repeated a thousand times becomes the

truth.” Another is “He/she who defines the terms wins the debate.”

Brown

may repeatedly attempt to pass off his view of the solar system as the only

view, but that does not mean the media or the public has to accept it. The

story of a possible new solar system planet can stand on its own, without endless

promotions of Brown and his book, parts of which stray so far from astronomy to

the point that he actually devotes an entire chapter to engagement rings!

If I

read a book about the solar system, the only rings I want to learn about are

those around planets or asteroids. I suspect many other astronomy enthusiasts

share that view.

One

of the view journalists who did go out of his way to be fair and balanced in

this story is Alan Boyle, author of the book The Case for Pluto. His article can be found at http://www.geekwire.com/2016/planet-nine-astronomers-boost-the-case-for-seeking-a-large-planet-x/?fb_action_ids=10154006841913189&fb_action_types=og.likes

.

In

that article, Alan Stern discusses what an actual discovery of a large outer

solar system planet would mean from the geophysical point of view. He says, “And

if it is found, it’ll confirm lots of work predicting the Oort Cloud is

littered with planets, and the solar system made dozens to hundreds of them.”

Anyone

who rejects the IAU planet definition or even just wants to acknowledge that

planet definition is an ongoing debate should simply refuse to call this object

“Planet Nine,” especially if it is actually found. Do not give Brown the power

he seeks to define the terms and thereby win the debate.

This

object would in no way replace Pluto, and its discovery has nothing to do with

Pluto; it would simply be a fascinating addition to our solar system, which has

room for many planets. That in itself makes for a fascinating story.

Tuesday, January 19, 2016

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)