Ethan

Siegel’s September 2, 2020, Forbes

article, “What Makes a Planet: Lessons Learned 14 Years after Pluto’s Demotion”

ironically indicates the writer has not learned any lessons from a decade and a

half of controversy and is simply doubling down on his insistence that Pluto

isn’t a planet, in spite of scientific discoveries over the last decade and a

half.

The

primary problem with Siegel’s article is its near-complete denial of the

continuing planet debate, blind repetition of the controversial IAU position,

and complete failure to acknowledge legitimate scientific opposition to that

position.

Siegel, an astrophysicist rather than a planetary scientist, misrepresents and

minimizes the community of planetary scientists who reject the IAU definition

in favor of a geophysical one with his statement, “Pluto doesn’t come close to

meeting the third criteria, and so only those who go by geophysical definitions

— where location and formation history are ignored — still consider Pluto a

planet in any way.”

That

last sentence is nothing less than denigration of the many planetary scientists

who prefer the geophysical definition with the false claim that they “ignore”

location and formation history.

Siegel’s assumed premise, that there are only three classes of planets—terrestrials,

ice giants, and gas giants, is false. This is the central weakness of his

article. He assumes there are only three types of planets because either he or

the IAU or both say so, without providing any supporting evidence for that

claim.

The reality is there are additional classes of planets, starting with the dwarf

planets. This term was initially coined by Alan Stern in 1991 to designate a

new class of planets in addition to terrestrials, gas giants, and ice giants.

When four percent of the IAU adopted their controversial planet definition

requiring an object to “clear its orbit” to be a planet, they misused Stern’s

term by stating dwarf planets are not planets at all but another type of object

entirely.

This claim is not borne out in New Horizons’ findings at Pluto or in Dawn’s

findings at Ceres. Both worlds are rounded by their own gravity and

geologically differentiated into core, mantle, and crust. Both have complex

planetary processes and probably belong in what should be yet another new

planet category, the ocean worlds—worlds with subsurface oceans that could

potentially harbor microbial life.

In

addition to his failure to disclose that orbit clearing was adopted by just

four percent of the IAU, most of whom were not planetary scientists but other

types of astronomers, Siegel also ignores the fact that the claim dwarf planets

are not planets at all was the decision of 333 individuals in a room on the

last day of a two week conference rather than some type of objective truth.

Beyond

repeating the claim that orbit clearing is a requirement for planethood, for no

reason other than the IAU dictated it, Siegel cherry picks classes of objects

he refers to as planets in spite of the fact that they do not meet the IAU

definition he so steadfastly supports. He seems to accept the idea that rogue

planets can be planets in spite of the fact that they do not orbit the Sun or

clear their orbits (they have no orbits to clear). He also seems to have no

problem referring to exoplanets as planets, in spite of the fact that they do

not meet the first IAU requirement, which is that a planet must orbit the Sun

as opposed to any star.

Most

of Siegel’s claims seem to be concocted by him, with no evidence to back them

up. For example, he refers to super-Earths as an “artificial class” without

justifying why he considers this class “artificial.” Analyses of exoplanet

discoveries made by the Kepler and TESS missions indicate super-Earth planets

with sizes between that of Earth and Neptune do, in fact, exist. We still know

little about them, including their percentages of rock versus gas, yet their

existence has never been disproven.

As

to the question of why our solar system does not have a super-Earth planet,

that is still a mystery. Scientists have observed a wide variety of exoplanet

systems, including some with multiple stars and some with several giant planets

all orbiting in different planes. They have discovered “puffy” planets, water

planets, hot Jupiters falling into their stars, and a wide variety of solar

system structures that suggest there very likely is more than one way for a

planetary system to form.

Significantly,

we have not yet found dwarf exoplanets, but that is likely because they are too

small to find with current technology. This will almost certainly change soon.

When exo-dwarf planets are found, will Siegel still hold to his claim that the

range of planet sizes is limited to “smaller than Mars and Mercury to larger

than the size of Jupiter?”

More

problematic is Siegel’s claim that Pluto somehow has a different formation

history than the larger solar system planets. This is pure conjecture.

According to a recent study cited by planetary scientist Phil Metzger, protoplanets

in early solar systems eventually grow large enough that their gravity stirs

the area around them, slowing their rotation rates until they accrete all the

material within their orbital zones. When they reach this stage, these

protoplanets become full planets or “oligarchs,” the largest objects in those

orbits. At this point, there are no other phases of planetary growth they fail

to reach.

Nearby

giant planets can keep other planets in their systems small by gobbling up

material from their orbits. Migration of giant planets in early stellar systems

can also do this. Both Mars and Pluto likely remained small because the nearby

giant planets accreted material from their orbits before they could. But other

than size, there is nothing inherently different between Mars and Pluto. Mars

has a smaller orbit to “clear” because it is closer to the Sun. The only reason

Pluto cannot clear its orbit is the fact that it is further from the Sun and

therefore has a larger orbit to clear.

Interestingly, calculations by planetary scientists confirm that if Earth were

in Pluto’s orbit, it would not clear that orbit either. This reveals a serious

flaw in the IAU definition—that the same object can be a planet in one location

and not a planet in another location.

Siegel and the IAU argue that Mars and Pluto are completely separate categories

of objects, yet both formed via the same processes. The only difference is the

amount of material that was near their orbits after they finished growing. This

is not a legitimate reason for putting these objects in two separate

categories.

Calculations by Metzger indicate that the hypothetical large planet in the

outer solar system, Planet X, would not clear its orbit even under the formula

cited by Jean Luc Margot and quoted in Siegel’s article, when it approaches its

closest position to the Sun, known as perihelion.

Furthermore,

Margot’s formula is flawed because planets can be in positions where they clear

their orbits only to be subsequently interact with other planets in their

systems and be ejected into much more distant orbits they cannot clear.

Contrary

to Siegel’s statement, the geophysical definition does not ignore an object’s

location. It simply does not make location a deciding factor for planethood. By

recognizing the non-dominance of the planetary subclass known as dwarf planets,

it acknowledges their location and dynamics while still classing them as

planets.

Meanwhile, Siegel and the IAU completely ignore dwarf planets’ intrinsic

properties, which are the same as those of the larger, rocky planets. Pluto is

70 percent rock, and Eris, being more massive, likely has a higher rock

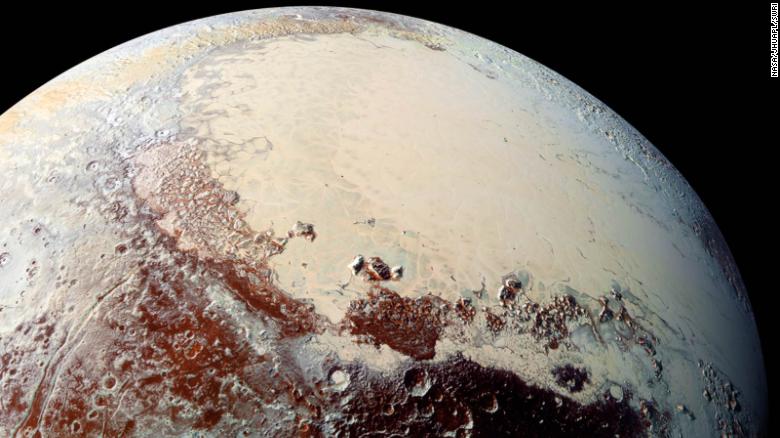

content. In describing New Horizons’ findings at Pluto, Siegel ironically reads

off a list of planetary characteristics—an atmosphere with hazes, ice mountains

and plains that float on top of a liquid ocean, snowy weather patterns, and varied

surfaces that change over time, but then goes on to discount all of these in

terms of making Pluto a planet.

At

the same time, Siegel has no problem lumping dwarf planets together with

asteroids and comets, which are very different objects, the latter not large

enough to be rounded by their own gravity, solely due to their locations. He

says Pluto fits in much better with the Kuiper Belt Objects while ignoring the

fact that there are two very different types of KBOs—one type large enough to

be spherical and the other not. The latter are loosely held together piles of

ice and rock, as opposed to the complex dwarf planets.

Siegel says regarding Pluto, “In many ways, it’s more complex and has more

potential for interesting chemical reactions — possibly even including

biological activity — than bona fide planets such as Mercury.”

In

other words, Pluto has a multitude of planetary processes and features but isn’t

a planet because the IAU says so??? How does any of this make sense?

The fact is, the IAU’s so-called “third criterion,” that an object must clear

its orbit to be a planet, was concocted for the sole, non-scientific reason of

keeping the number of solar system planets small and excluding Pluto.

In summary, Siegel’s claims that our solar system has only eight planets and

that from the perspective of astronomers, Pluto was never a planet at all is

nothing more than an appeal to authority—which is exactly the opposite of the

scientific method!

Most astronomers do not study planets. Should planetary scientists tell those

who study black holes what a black hole is and is not? Asking astronomers who

study completely different fields to define planet makes no sense. It is akin

to asking podiatrists to define brain surgery.

After 14 years, here we are—at the same place we were in 2006 but with a lot

more knowledge of Pluto, thanks to New Horizons. The IAU and Siegel cherry pick

the data they want and use circular reasoning to make their points. None of that

makes dwarf planets, including Pluto, any less than a subclass of full planets.